The world after liberal hegemony

Towards the rise of a post-Western revolutionary horizon.

by Youssef Siher

Western modernity, in the form it took between the end of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st, is undergoing a phase of radical transformation that is not limited to questioning some of its political or cultural categories, but touches on the very foundations of the way in which the West has thought of and described itself for centuries. What we call today a “crisis” is not a sudden event or a side effect of globalization, as is often suggested in public discourse: it is rather the emergence of a structural fracture that has been inscribed in modernity since its inception. This fracture coincides with what Frantz Fanon described as the ontological division between fully recognized human beings and human beings produced as inferior, deprived of full subjectivity, confined to a space of non-being. Modernity, in its Eurocentric version, was built precisely on this original gap. For centuries, Europe was able to project its political and moral order onto other continents only because it had defined as “others” those peoples who were subjugated, administered, and exploited. Colonial violence, both physical and symbolic, therefore represents not an accident but an essential operation for the self-representation of the West as a space of reason, progress, and civilization.

Today, however, this distance no longer holds. Populations that had been confined to the margins of the global system now find themselves within the social, economic, and cultural spaces of the West.

The colonial border, which for centuries allowed Europe to imagine itself as the “neutral” center of the world, has entered into crisis.

And the crisis of the border is always a crisis of identity: it is not simply a migratory phenomenon, but an epistemic event. It is from this collision between modernity and (post)coloniality that what the Peruvian sociologist and thinker Aníbal Quijano defines as “coloniality of power” takes shape, that is, the persistence of colonial logics in contemporary societies, even in the absence of direct territorial domination. Coloniality is not a remnant of the past, but a structure that reproduces itself through languages, norms, knowledge, and institutions. It is the way in which the West continues to assign itself a central role, continually redefining racial difference in new forms compatible with liberal democracy, capitalist economics, and neoliberal governance.

Aníbal Quijano

The metropolis as a new colonial space

The place where this transformation is most evident is the Western metropolis. The large European and North American cities of the 21st century have become spaces where the colonial legacy manifests itself not only as historical memory, but as a living structure that organizes everyday relationships.

The emergence of an increasingly visible presence of racialized subjectivities—migrants, refugees, second generations, diasporic communities—is not simply an effect of global population movements, but the internal return of a history that the West had relegated to a colonial elsewhere.

Metropolises thus become veritable laboratories of colonial-like governance: spaces in which the logics of control, exploitation, surveillance, and discipline that had been developed in overseas colonial administrations are re-inscribed.

Contemporary cities are divided by lines that are not only economic or cultural, but openly racial.

The distribution of poverty, precarious housing, access to social services, and economic opportunities follows maps that closely mirror the global racial hierarchy. The suburbs, the banlieues, the working-class neighborhoods become spaces of symbolic and material confinement, where racialized presence is tolerated only within certain margins and always under implicit or explicit surveillance. What these forms of government have in common is the production of subordinate inclusion. It is no longer a question of the nineteenth-century logic of total exclusion, but of a logic of hierarchical incorporation. In other words,

the racialized subject is recognized as part of society, but in an inferior position:

as a necessary worker in low-wage sectors; as a functional symbolic figure in political discourses on security; as a marginal consumer; as an aestheticized presence in cultural narratives that exhibit diversity without changing the balance of power. In this context, the (post)colonial city is not a neutral place or a simple meeting space between cultures, but a territory where a hegemonic battle is being fought over the very meaning of citizenship, coexistence, and social justice.

Race, capital, and the crisis of Eurocentrism

To fully understand the structure of this situation, we need to rethink the relationship between race and capital. The traditional Marxist interpretation, centered on class division, has been decisive in analyzing the relations of production in European industrial society, but it appears insufficient for understanding the structural link between capitalism and racialization. Marx wrote in a world where Europe was still the material center of the world economy and where the presence of colonized peoples within Europe was marginal. Today, the situation is radically different.

Race, rather than class, defines access to resources, opportunities, and social recognition. Not because class has disappeared, but because racialization precedes and structures the placement of individuals in production relations.

Fanon grasped this with extraordinary precision: “It is clear that what divides the world is first and foremost whether or not one belongs to a given species, to a given race. In the colony, the economic infrastructure is pure superstructure. The cause is the consequence: one is rich because one is white, one is white because one is rich.” To paraphrase, in the colonial world, one is not exploited because one is poor, but poor because one is racialized. Race is the original matrix of social division, and capital is grafted onto this division, not vice versa.

Puerto Rican sociologist Ramón Grosfoguel has radicalized this insight by showing how Western modernity exercises global epistemic control, imposing its own criteria of truth, its own categories, and its own methods as “universal” and “neutral,” when in fact they systematically exclude knowledge produced by non-European peoples. This epistemic racism is perhaps the most profound dimension of coloniality: it does not merely discriminate, but decides who has the right to know and who can be considered the object of knowledge. Eurocentrism, in this perspective, is not a cultural prejudice, but a grammar of power.

As Gramsci showed, cultural hegemony is exercised precisely through the ability to define what appears spontaneous, natural, or inevitable.

The West, through its global network of universities, international institutions, media, and cultural industries, continues to present its worldview as if it were the only one possible, even as social reality increasingly contradicts it.

The crisis of Eurocentrism is therefore a complex process: it does not coincide with the end of Western domination, but with the West’s growing difficulty in maintaining its epistemic monopoly. The categories with which it has interpreted the world, from the social sciences to identity politics, are now showing their inability to interpret the complexity of (post)colonial societies and to reimagine other forms of life, both in the countries of the global South and within Western metropolises.

New imaginaries in the peripheries

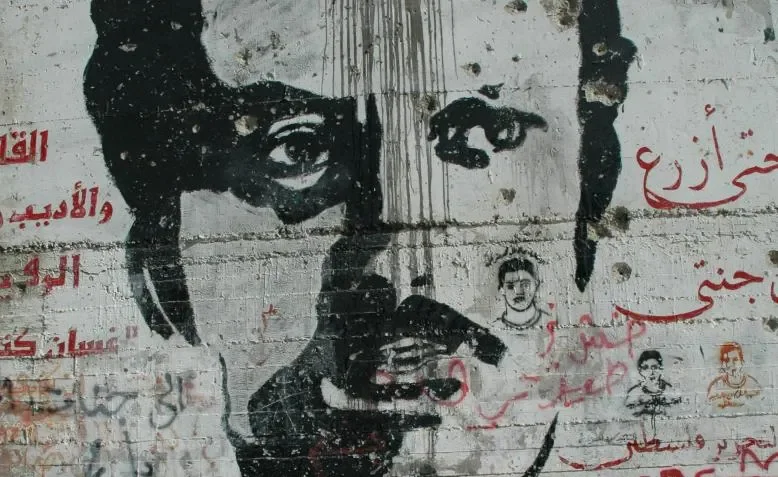

Despite the persistence of racial hierarchies, new forms of collective subjectivity are emerging in global and urban peripheries that challenge the hegemonic and dominant narrative. Palestinian writer and intellectual Ghassan Kanafani described this dynamic in his study of the Palestinian struggle, showing how

Ghassan Kanafani

political transformation does not come from elites integrated into the colonial system, but from the popular classes who experience oppression firsthand.

This insight is valuable for interpreting contemporary movements: it is not from institutions or globalized middle classes that the deconstruction of coloniality can come, but from life experiences that concretely challenge the racial hierarchy.

In Western metropolises, new forms of solidarity are formed every day that do not correspond to traditional political categories.

Alliances between young people of migrant origin, indigenous populations in diaspora, Afro-descendant communities, and racialized workers are not limited to claiming civil rights: they produce new aesthetics, new languages, and new narratives of history. Music, fashion, urban culture, mutualistic practices, struggles for housing or against police violence are places where imaginaries capable of escaping the control of Western hegemony are developed.

These imaginaries, often transcending nationalities and religions, represent what Ibn Khaldun, one of the greatest Arab thinkers and founding father of sociology, would have called a new form of ‘asabiyya, a force of cohesion that allows marginal groups to overturn the established order. Western modernity, for its part, shows clear signs of weakening its own ‘asabiyya: it is no longer able to produce consensus around its own narrative of the world, nor to contain the real plurality that runs through its societies. The struggles that arise in the suburbs are not merely reactive, but revolutionary. They construct a worldview in which plurality is not a problem to be managed but an original condition; in which race is not a criterion of hierarchy but a historical trace to be deconstructed; in which modernity is not a single model but a field of possibilities that opens up in many directions.

The end of a hegemonic device

Total exclusion or subordinate inclusion, which have played—and continue to play—a fundamental role in the history of Western modernity, are now categories in crisis. Not because race has disappeared, nor because racism has diminished, but because the mechanisms of subjectivity production are changing. Western society is no longer able to organize its hegemony according to the dichotomous logic that for centuries separated white people from subordinate humans. Race remains a fundamental structure of inequality, but its functioning is less stable, less secure, less effective.

Attempts to reproduce the image of the internal enemy through increasingly aggressive security measures, through the militarization of the territory, and through alarmist media campaigns are signs of the fragility of the hegemonic order, not of its strength.

We are therefore in a historical transition in which Western modernity is no longer able to represent itself as the destiny of the world. Its crisis is not only political or economic, but epistemic. It is a crisis of a way of knowing, classifying, and ordering reality. In the void that this crisis opens up, new epistemologies emerge, often born on the margins: indigenous, Afro-descendant, diasporic, decolonial, and non-Western epistemologies. These are no longer peripheral voices, but emerging centers of meaning production.

The grammar of the world to come will not be a reformulation of Eurocentrism, but its radical deconstruction and total reversal. It will be a pluriversal modernity, which will not have a single center and will not assign the West the role of arbiter of meaning. It will not necessarily be a more just world, because justice does not arise spontaneously from the decline of a system of power; but it will be a world in which the very definition of justice will be contested by a multiplicity of subjects who refuse to be reduced to subcategories of the human. The West can decide to face this transformation by recognizing the structural nature of its crisis, or it can attempt to tighten its control mechanisms, fueling permanent internal conflict. In either case, the transition is already underway. Its forms will be determined by the ability of racialized societies to produce new knowledge and new institutions. And it will be from these experiences, rather than from established theories, that the new grammar of reality will emerge.