Decolonizing violence to understand Palestinian Resistance

by Camilla Donzelli

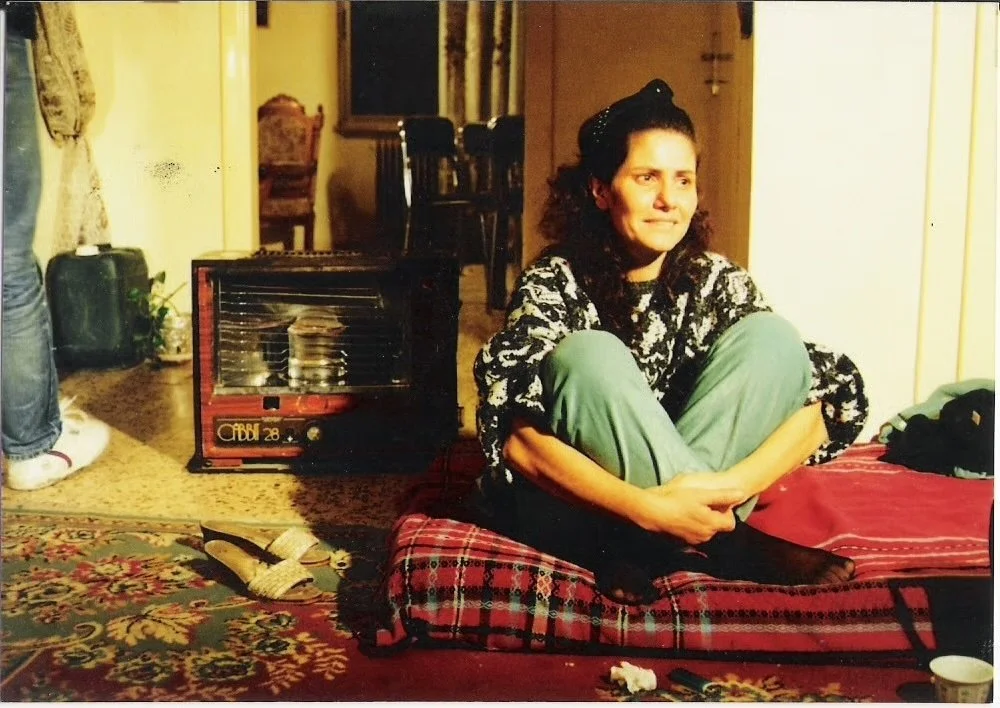

In 1993, filmmaker Arab Loutfi conducted over 35 hours of interviews with seven women who, over nearly three decades, played a crucial role in the Palestinian resistance. In 2007, those interviews gave life to Tell Your Tale, Little Bird, a remarkable documentary that restores voice and memory to Palestinian women involved in the armed struggle. Among them is Leila Khaled, a prominent figure of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, known for her participation in two airplane hijackings in 1969 and 1970.

“Sometimes things make you laugh”, Khaled reflects. “They call people fighting for their rights terrorists, while a state organizes terror against a nation, and we don’t call that terror; we call it self-defense.

We have begun to define what is and isn't terrorism. If we take Europe as an example, everyone carried weapons against the Nazis. That’s history—their history. Why is this resistance considered legitimate, but others are not?”

Unequal resistances

Rosario Bentivegna was a partisan active in the Gruppi di Azione Patriottica (“Patriotic Action Groups”). He is best known for his role in the Via Rasella attack, which killed 33 SS soldiers and was used as the pretext for the Fosse Ardeatine massacre. After the end of the occupation, Bentivegna was tried, and the case ended in his favor. In 1957, Italy’s Supreme Court of Cassation classified the Via Rasella operation as a legitimate act of war.

On the website of the National Association of Italian Partisans (ANPI), Bentivegna is remembered as a “fighter”, one of the “most valiant protagonists of the Resistance.”

In the wake of October 7, 2023, however, the same ANPI, through a statement issued by its national secretariat, described Hamas’s attack as “mad and irresponsible.” While acknowledging the existence of an occupation, the text called for “a just and negotiated solution” that could guarantee “peace and coexistence,” urging an immediate halt to “the attack on Israel.”

A year later, in the midst of the ongoing genocidal assault on Gaza’s population, ANPI president Gianfranco Pagliarulo struck a similar tone. He described Hamas’s attack as “the death of compassion,” “an act of barbarism” targeting victims chosen “because they were Israeli.”

The same ANPI that rightly defends the memory of the Italian Armed Resistance now proves unable to recognize the right of another people under occupation to resist. The language it uses drains any radical opposition of meaning.

This position is not an exception. Over the past two years—especially within spaces that call themselves progressive—solidarity with the Palestinian cause has become increasingly conditional. In both public and private debate, before expressing support, many feel compelled to distance themselves from that form of Palestinian resistance that resorts to violence.

“The dominant imaginary expects that the colonized, if they want to be deemed ‘worthy’ of support and compassion, must be silent victims—suffering but not dangerous, capable of inspiring pity but not fear,” Palestinian activist Donia Raafat commented.

“The colonized who react with force disrupt the hegemonic narrative: they cease to be a passive object and become a political subject. And that frightens, because it destabilizes the myth of the West’s moral and political superiority.”

The demand for docility from those enduring colonial violence is not a new phenomenon. Over time, it has solidified and radicalized, fueled by global narratives that portray every form of non-white resistance as a threat that must be neutralized.

Hamas was added to the U.S. list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations as early as 1997. A few years later, following the September 2001 attacks, the era of the “War on Terror” began. As Francesca Albanese and Christian Elia explained in their book J’accuse, it was precisely during this period that then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon capitalized on the global climate to forge a media-political propaganda that radically reshaped the image of Palestinian resistance.

What had been a struggle against colonial oppression was reframed as yet another expression of Islamic extremism, to be treated as a “security issue.”

The European Union, self-appointed guardian of human rights, wasted no time aligning with this narrative. It has refused to isolate Israel, openly condemn its genocidal campaign, or acknowledge the systematic destruction of Gaza. Instead, it has continued to legitimize Israel’s security discourse and stigmatize Palestinian resistance. As early as January of 2024, the EU Council had already imposed sanctions on Yahya Sinwar, the political leader of Hamas, deemed directly responsible for the October 7 attack. Sinwar was killed on October 16, 2024, in a confrontation with Israeli occupation forces.

The total criminalization of Palestinian resistance does not stop at the borders of Gaza or the West Bank; it extends into the diaspora, further obscuring the anti-colonial struggle.

A striking example is that of political prisoner Anan Yaeesh. The 37-year-old Palestinian has lived in Italy since 2017 and was granted refugee status after being tortured by Israeli authorities. Yet, he has been held in L’Aquila prison for over a year, accused of financing the Tulkarem Brigade, an armed group active in the West Bank. Paradoxically, the case file is based entirely on evidence provided by the same Israeli authorities responsible for Yaeesh’s persecution. Once again, the charges fall under the category of “terrorism.”

As Donia Raafat noted,

“The way we judge colonized populations, and the selectivity with which we support certain people based on a colonial hierarchy, says more about us than about them.”

It reveals neocolonial narratives and frameworks that were never abandoned.

How can we begin to interpret violent Palestinian resistance not as an anomaly to be condemned, but rather as a human and political gesture of refusal against annihilation?

Recontextualizing, rehumanizing

“It is not violence itself that must be sanctified, but the fact that in certain contexts there is no other way to be heard, to demand justice, to put an end to a dehumanizing relationship,” Donia Raafat explained.

In this sense, the Algerian liberation struggle offers a historical precedent with much to teach us. Beginning with the National Liberation Front’s insurrection in 1954, it lasted eight years until independence was declared in 1962. During this period, the tactics adopted by the Algerian resistance included a widespread use of violence: bombs and armed attacks targeting the European quarters of Algiers, occupied by French settlers.

In 1966, Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo released The Battle of Algiers, a film that retraces events from 1954 to 1960. With almost documentary-like precision, the film provides the necessary context to fully grasp the political meaning of the FLN’s violent actions.

Through the eyes of Ali Lapointe and other Algerian fighters, the narrative moves through the narrow alleys of the Casbah of Algiers, capturing the essence of a society built on systemic racism, oppression, segregation, and dehumanization. Within such a reality, the violence carried out by the FLN appears as a necessary response to a system that leaves no room for alternatives.

There is no glorification of violence in Pontecorvo’s story. What emerges is the understanding that in a colonial context, violence is never an isolated act but always a reaction to an original and structural oppression. It is colonialism that inaugurates violence, and every act of resistance is born as a response to that founding brutality.

The fighters are thus rehumanized: not monsters, not fanatics, but men and women who choose to struggle because every other path has been systematically denied.

The same applies when we talk about Palestine: it is crucial to recontextualize. As Donia Raafat stressed, “Asking Palestinians to be ‘peaceful’ is not a request for peace, but a request for moral surrender.

Asking Palestinians to be peaceful without first ending occupation, apartheid, and colonization is one of the most hypocritical positions one can take. Pacifism, if it is not accompanied by justice and the end of domination, is not ethical.”

Aisha Odeh, a protagonist in the documentary Tell Your Tale, Little Bird, was arrested for placing explosives in Jerusalem’s Supersol supermarket in 1969. She recalls a fragment of a conversation from her interrogation, which resulted in her receiving a life sentence. When an officer asked her why the Palestinian liberation movement had chosen to take up arms instead of pursuing diplomacy, Odeh replied: “When you entered our country, you were not political; you used tanks and weapons. So it is natural to resist your presence with the same weapons. Your country was based on terror, so don’t argue about this point. We do not argue about what we are doing; it is our right to resist.”

In his book Decolonizing Palestine, anthropologist Somdeep Sen provides a theoretical framework for the use of violence in the Palestinian liberation struggle.

Sen explains that

a defining feature of settler colonialism is the deliberate denial of the existence of the Indigenous population. In the case of the Zionist project, this has meant the physical erasure of Palestinian people and spaces, as well as a series of “minor” strategies aimed at cultural oblivion.

Consider, for example, the appropriation of Palestinian culinary traditions or the total absence of Palestine and Palestinians in museum exhibits celebrating Israel’s so-called “War of Independence.”

Based on this premise, Sen builds on Frantz Fanon’s work to argue that anticolonial violence has two functions: destruction and creation.

Although Hamas’s military capabilities are vastly inferior to those of the Israeli occupation forces, its persistent armed struggle creates cracks in the colonial structure. Hamas challenges Zionist dominance and its perception of being unshakable, making the maintenance of the occupation more difficult than expected. In this sense, Hamas is destructive.

Perhaps even more importantly, a violent reaction can generate a collective consciousness. In a context of constant annihilation and erasure of Indigenous identity, armed struggle produces its own codes, languages, and objectives. Thus, the act of resistance becomes recognizable as a Palestinian act of resistance. Through violent reaction, Palestine and Palestinians finally exist and become visible despite the colonizers’ efforts to erase all traces of them.

In the words of Rashida Obeida, another protagonist of Tell Your Tale, Little Bird, armed resistance is an act of reclaiming one’s capacity to act, opening the door to future possibilities. Obeida recalls a letter from her partner, Sobhi, who wrote: “We should not just observe what takes place; we should be the ones who make it happen. Our role is in the process of change. We should not watch incidents but perform them.”

Decolonizing violence

Decolonizing violence means exposing the moral and colonial hierarchies that dictate who is permitted to use violence and who must silently endure it in order to be considered “worthy” of solidarity.

First, we must interrogate our own positionality and acknowledge that demands for pacifism and reconciliation stem from privilege—the privilege of those who do not experience occupation firsthand.

“In order to build forms of radical solidarity, we must first unlearn our role as moral spectators and take on a position of political responsibility. We are not neutral; we are part of global systems that produce and sustain oppression,” Donia Raafat concluded.

“Radical solidarity means creating concrete support networks, amplifying marginalized voices without censoring them, supporting the right to resistance even when it is uncomfortable, and, above all, ending the demand that oppressed peoples be presentable, polite, and not too angry or radical. True solidarity does not tame rage—it honors it.”